I will start by telling a story. As of late, most talks about historical memory have become practically impossible to carry without telling stories – the stories of common people, who just speak about their lives. That’s odd, because historical memory is a superindividual phenomenon, something we “remember” together, as a collective, something usually not related to our personal memory.

My good friend and brilliant literature scholar from Odessa, Anna Mysiuk, told me that she had once been invited to a family evening in Israel, into a family of Moroccan Jews. The relatives had gathered together to commemorate their grandma’s death anniversary. For this occasion, the grandchildren had published a book with their grandma’s recipes – they had collected the ones they still remembered, had put them in a book, and even cooked some of the dishes for this family evening.

Anna told me she had suddenly realised that her family would not have been able to do something like that. Collecting such everyday bits and pieces like family recipes is possible only when a natural connection between generations exists. “That would be impossible for us”, said Anna.

“Our memory is torn apart. No one ever told me stories about the life before or during the war, or about their ghetto experiences.” Anna once asked her mother why she would not tell them. The reply was: “Because you should be able to live together with people, and not be afraid of them.” We are now even with the past. Pages are turned. And memory is torn.

The 20th century became a century of torn memory. And it was, probably, the very sensation of these torn memories that made theoreticians notice the phenomenon of collective memory and look closer at it. Do you remember Holmes explaining to Watson that we notice something only when it breaks? We take things for granted when they “work” properly. How many steps lead up from the hall to our room? Usually, we do not remember. But as soon as one of them is broken, then we would know that for sure.

The same applies to the collective memory. As soon as memory starts to tear apart, we begin to stare at this rupture and try to figure out what is going on. It’s no surprise that the first researches of collective memory were made between the two world wars. When surviving becomes an issue, when individuals are constantly looking for shelter or anxiously waiting for the news from their loved ones in the army; then the peaceful experiences cease to exist. Memories become irrelevant. The world before the war seems unreal now, it takes an effort even to believe it ever existed.

Several years ago this subject was of purely theoretical interest to me. It was enlightening to read, for example, about the research made by Igor Narsky about how the historical memory formed during the Civil War in the early 1920s in the Ural region (1). Back then, the five years of destruction of the usual life and the lack of stable communications with the outside world had caused not only the raptures in memorization, but they also formed an intricate ideological construct that was sincerely accepted as memory. People had conformed with remembering the five years of development of the Soviet government in the Urals. Now I understand too well what’s it like to not be able to restore my own life plans and motivations from before the year 2014. The memory tore, and not only individual memory did so. Common memories are building new points of entry – if we had been told 5 years ago what would these points look like, we’d have never believed such nonsense.

It’s a bit funny to realise that it was not the first time such things happened. That the very notion of collective memory had begun with the attempt to cope with the rupture of memory. Immediately after the World War I, most European nations started to stitch back the fabric of history that had suddenly refused to demonstrate the familiar picture of moving towards the better living. The History had broken.

I will refer here to the philosopher Bernhard Waldenfels’ conclusions. Any “breaks” of the familiar (inhabited, automatically interpreted) world can be described using the metaphor of a wound. Physical intrusion calls for my attention (2), withdraws me from the automatic daily existence. Waldenfels sees the peculiarity of the state of enduring in the fact that, in this case, meaning sinks in the real intrusion – something interrupts our speech (3). In the case of enduring, we approach the limits of human existence – we must either overcome somehow the negative influence or die. Existing in a reality that we cannot recognise in its alienness is unbearable.

If the inhabited world’s loss of inhabited contours did not result in death, the opportunity to start “healing” it arises. “The time is out of joint: O cursed spite / That ever I was born to set it right!”, these words by Hamlet describe precisely the act of restoring order, rebuilding the world’s image that was destroyed by an intrusion of a terrible crime. The first step for setting it right would be the interpretation (even a wrong interpretation helps when starting the process of healing). Then, the interpretable elements can be used to build new images. The same happens to the memory ruptures – old templates do not work anymore, so, in order to heal this rupture, we need to discover new interpretations and embed them into the old templates of understanding the meaning of History.

When European History “broke” after World War I, they started to heal it. Enormous efforts were undertaken to stitch back the torn fabric of collective memorization via embedding new symbols into the traditional contours of identity. Thus, in 1918 the figure of the Unknown soldier was invented, and it became sacred for the people in the 20th century. The tombs of Unknown soldiers became that medicine which allowed to draw a connection between the military glory of the old time rulers and the mourning over the countless victims of the world war. The way the cult of the Unknown soldier functions is immensely complex and symbolically saturated. Taking a closer look at the ceremonies of establishing the first tombs of the Unknown soldier in London and Paris, we would notice rough symbolic stitches on the newly restored fabric of memory.

The British soldier was chosen so that he could really be the average unknown British soldier who had accepted his nonhuman burden. He was buried next to the kings (the past symbols of Britain), was transported on a hearse made of royal oak and decorated with the cross-bearing sword from the royal treasury. Not only that, the acting British monarch had chosen the sword himself. Somewhat later a tradition was established, when the brides from the royal family started to leave their bridal bouquets at the Unknown soldier’s tomb – therefore it was right here that the Britain’s past and future were being symbolically linked, again with the image of the grateful monarch. The French Unknown soldier was honoured by an additional powerful symbol – the Eternal fire, which linked the warrior’s heroic deeds with the glorious Roman temple of Vesta (the goddess of domestic fire), where the imperium, the symbol of the emperor’s authority, was stored.

Nowadays, we no longer see the traces of the rupture – the scars of the fabric of history have healed, presenting us both the Eternal fire and the Unknown soldier’s tombs as perfectly “natural” and traditional elements of commemoration. But in the 1920s, these stitches were laid onto the scars so thoroughly that the very nature of historical commemoration had changed. Only the description of the several days long ceremony of the repatriation of the British Unknown soldier would take a good ten pages – the contours of the new way of existence interpretation were being drawn with great care and attention.

It’s possible that the very state and the hard work of reloading the common memorization had caused also the theoretical re-framing of a phenomenon that had existed always, but was untraceable due to its natural reproduction. At the end of the 1920s, Maurice Halbwachs had developed the concept of the historical memory being a shared pool of knowledge about the past, to which a certain community holds the interpretational keys, and which is being reproduced using specific instruments (from school textbooks to official monuments). Halbwachs was observing this phenomenon directly at the times of its breaking, refusal to function, and works on its repairs.

Sometimes the efforts to stitch back the torn “natural” memory cause frustration. I’ll recall here the famous concept of “sites of memory”, popularised by Pierre Nora, one of the most prominent researchers of historical and collective memory in the 20th century. Nora describes the emergence of the “sites of memory” (memorials that exist not just as monuments but also as centres of ceremonies, in which schoolchildren and officials of various levels must participate obligatorily) as a result of the failure in the “natural” collective memory functioning, when stories told by elderly family members complement the information obtained at school. In the 20th century, the society’s development loses its “natural” contours (add here the industrial progress which fuels mobility and loosens family ties), and the collective memory starts to experience the need of “external” support – specifically established places where the serious attitude towards the state history is practised. Pierre Nora observed the lush ceremonies at the “sites of memory” that were meant to form the identity of schoolchildren, demonstrate the state’s political position, etc. The “unnaturalness” of such sites, after Nora, causes their lack of life. They are full of boredom and deadly seriousness. Any attempts to look at these sites from a different angle, to alter the ways of honouring the past, can cause indignation and are perceived as a desecration. For me, it’s important here that Nora reacts towards one of the effective tools of fixing the ruptures in historical memory, describing it as a strictly contemporary and artificial phenomenon. The “Sites of memory” were instituted by states in an attempt to fix the torn memory and restore the holistic image of the world. These sites were fit to support the identity through connections with the past.

The historical memory in the last century has been in a constant state of being ruptured and then being fixed again – and not only due to world wars and their inconceivable indifference towards human lives. The 20th century has also produced parallel historical memories that try to survive under the state pressure. The memory about crimes committed by political regimes is preserved not at the “sites of memory“, because authorities tend to silence such memory – but where? Here I’d like to quote the works of the German researcher Aleida Assman, who had pointed out that historical memory is multilayered (4). The image of the past that has the official support of the state (in general) through education, memorialization, and public ceremonies, forms also the so-called canon of memory. This canon inevitably pushes out of sight everything that seems insignificant from the “official” point of view. Let’s recall, for example, the memory about the sufferings of the German civil population during the World War II. It was stored in the “archive”, so, speaking out loud about the crimes committed against the German civilians was deemed unethical. In comparison to the extermination of the European Jews and millions of victims in the USSR and other countries, any mentions of the raped German women seemed to be awkward. Archives and canons can switch places when the general frame of values in the society changes. Günter Grass’s novel “Crabwalk” allowed us to take a closer look at the terrible consequences of silencing the tragedy of a common human being. The injury that they keep inside can become a weapon. The stitching of the “memory ruptures” here lies in giving a voice to the “archival” knowledge. It was initiated in its time first by Günter Grass and then by the TV miniseries “Unsere Mütter, unsere Väter”, which allowed different generations of Germans to finally engage in a common conversation.

In general, any traumatic experience has more chances of becoming the “archive” than the “canon”, thus contributing to the formation of the rupture. During the first years after the event, people tend not to talk about the trauma. They don’t recall it, because it’s still too painful. The memory about the war goes to the archive, the canon is not yet ready to accept it. In Israel, before the early 60s, they tended not to touch the subject of the Holocaust – because there was no language yet to talk about it. The traces of any war are likely to be removed as soon as possible, in order to start living normal lives again. A good example of this happened when one of the Leningrad Blockade’s researchers noticed that the wall signs, which marked the safest side of the street during the shellings and had been preserved from the war, were painted in black, while one of the Blockade’s eyewitnesses in her memoirs described them as brown. When asked, the author of these memoirs had pointed: “These are not our signs. Ours were painted over immediately after the war. And these were restored some 20 years after.” (5) When the trauma is granted the right to be in the canon, the visible traces of suffering this trauma are restored (in this case, this was a way to prevent the memories of the victory from vanishing). I have allowed myself this digression towards the “mild” archive to highlight the difference between remaining silent about something “currently irrelevant” and a total deprivation of voice.

Members of the repressed groups tend to preserve their memory in a “counter-memory” mode (also called “anti-memory” or “archive of memorization” – different researchers have different names for it), guarding heavily the borders of their personal space. It can often be dangerous. The declaration of a certain position can cause repression towards those who try to voice it. And this produces a new rupture – when parents choose not to tell their family history to their children so as to protect them (in case they unintentionally let it out) or even to hide their own crimes. Those who had lost their relatives in the camps for political prisoners often chose not to pass this experience on to their children. The soviet ideology was built in such way that it was considered a shame to have a relative prosecuted for political reasons. In German post-war families, the events that had occurred during the World War II were covered with silence. All this was reinforced by the authorities’ reluctance to acknowledge the existence of the issue. And these were the causes that led to the memorization rupture.

Any rupture calls for fixing. The German post-war silence was broken by the rebellious generation of the 60s, which accused their fathers of complicity in the war crimes and refused to accept their family ties. Parents kept silence while children were constructing their own memory. The descents of the repressed persons during the “thaw“ and “perestroika” periods were able to find out about the regime’s crimes from the publicly available data, and then started asking themselves – where is my family’s place in this whirlpool? Why some subjects still remain forbidden?

A person, upon finding themselves at this point of their quest, gathers something out of which the memory can be created. They do not have their grandparents’ or parents’ stories, family photos or archives, nor any objects related to some personal stories. They have empty gaps filled with silence instead. Gaps where the hidden memory begins. They complete their own family history based on external sources. Therefore, it is not a memory as we used to think of it. It is a construction made to serve as a memory prosthesis, so it can replace the amputated piece of familial memories. We will find many such prostheses in the contemporary world, they even have a name of their own – the American researcher Marianne Hirsch calls them postmemory (6). Postmemory is not equal to memory, it is a 100% artificial construct used by people to fill the information gaps which appeared in their familial history due to omissions or loss of relatives.

What purpose do these long searches in the area of collective memory ruptures serve? What I meant to do was to define the contours of the possibilities of looking at the memory. It becomes the centre of attention when it breaks and refuses to perform its functions. The concept of historical memory had been developed after the powerful break of history in Europe when serious efforts were made to fix the identificational potential of knowledge about the past. The number of efforts that had to be taken during the last hundred years to rebuild the memory as a useful tool shows us how important memory is for a contemporary person: it is something they can rely upon when getting to know themselves. Each time the sensation of rupture produces the feeling of losing the ground beneath one’s feet, they desperately seek ways to restore the connection with the past.

For the past three years, the memory in Ukraine has been undergoing something we’ve never seen before, despite the extremely vast European experience of stitching back the ruptures in the fabric of memorization. In 2014, Ukraine was put under a test we were not prepared for. We were not even prepared to believe this was happening for real. When people were leaving the territories that had become unsafe, it seemed to be temporary, only for a couple of weeks, not even months. Those who were leaving could not care less to take with them their family albums, relics or heirlooms. It’s not for long, we will come back, they thought. But they didn’t. At some point, people began to understand that they had lost their home, even if the home still existed physically there, and even if they could return in the future and find it standing. For them, the home had ceased to exist. There are few ways for us to comprehend the memory these people lost. Earlier I was describing the enormous efforts undertaken by the 20th-century people to restore their memory – an important experience, which nevertheless lacks the vision of displaced people. An untrained gaze would look past such triviality as family albums.

But time passes and memory starts to work. At some point, the question “when do we go back?” is joined by another question – will there be this “back”? For sure, the construction of new contours of memory about home marks the moment when it becomes clear that there will be no coming back. The memory about home becomes something full and complete. However, this memorizing requires “braces” around which images are built, so they can later be turned into complete stories. Our identity has to become a story, otherwise, it is almost impossible to explain who we are. Stories about the past cannot live without illustrations – that is why monuments are built and memorial signs and plaques are installed. We can read the past in them. But upon what can the memory be built by those who have just realised that there is no more home?

After the World War I a heroic figure was invented, one that was later carefully linked to the traditional historical senses. In the case of postmemory, people complete their own familial memory with the available materials from other people’s past. Even without asking for their consent.

Did the Unknown soldiers want to rest next to kings and eternal fires? Did the repressed people want to share their lives to complete the memories of those whose relatives either were silent or perished? Can we speak about these operations in terms of violence or occupation of somebody else’s memory?

When we rebuild our memory and restore the bonds with the past to fix the broken world, we inevitably perform an act of occupation. The first step on this path is painful, it blurs the contours of the inhabited world. Moreover, it is painful not only for the one who is attempting to restore the memory, but also for those who stand nearby. Why do it then? Isn’t it more in the human nature to avoid pain and seek a safe place where nothing can get to us?

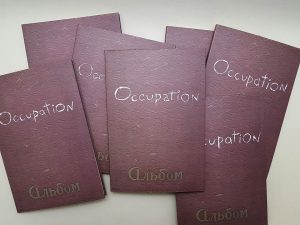

These were the questions that the “Reconstruction of Memory” exhibition put before me, and it started with Andrii Dostliev’s project “Occupation”. Occupation seems to be just the right word to describe the process of creating some new ground under your feet, instead of the one that was left in the occupied territory. Similar to the processes of postmemory, the images of the author’s own past are reconstructed here with the help of other people’s materials. But in the case of Dostliev’s “Occupation”, the author knows for sure what he remembers, but he cannot share his knowledge because the family albums and memorabilia remain beyond reach. The memory has preserved every single fragment of the family photos but is unable to show them! The artist makes a strange move here, at least at first glance: he buys at the flea markets old photos of people he doesn’t know, and he fills them with his own stories, painting over and combining. Therefore, he occupies them.

The artist doesn’t just use random photos of other people – they are also a trace of a certain layer in the collective memory. In every family album, there were “typical” topics: trips to the capital city or to the “south”, visiting relatives in the countryside in summer, semi-naked kids, group photos of school classes and co-workers, etc. We recognise these topics – there are identical ones in our own family albums. It becomes easy to take somebody else’s photos and paint over them a dress that grandma had or your own toy from childhood.

“Occupation” causes a strange impression – you arduously observe the process of restoring memories through the adjusting of the frozen moments of other people’s lives and, at the same time, stare into the faces of people whose photos were being sold as antiques. These people have also lost their families – and now they have obtained a new live in new memories. It is a certain solidarity of the displaced. It seems that Andrii Dostliev’s “Occupation” turned out to be the most “theoretically” profound work in the project, which calls for becoming a part of the didactic material in the course of memory studies – it is a sincere text that should be read with all the notes and references. And it is also a certain interpretational key to the whole project, despite the vast spectre of messages transmitted by the artists.

I have read a bit about the exhibition before attending it and, therefore, I already knew what to expect – but it still managed to surprise me. I was expecting the least from Victor Corwic’s “Airport Donetsk”, because what can one expect from VR model which was initially made as a part of the architectural project for the new terminal of the airport. What worried me the most, in this case, was that my emotions would be manipulated – because the airport does not exist anymore, it became a symbol of both extreme courage and sadness for Ukrainians, and I was about to see it still standing. That is why I put on the headphones and peered into the VR glasses rather out of sheer curiosity. And I discovered myself in a constellation of senses I was not ready for. Prokofiev, whose name the airport was bearing, Sting’s song based on Prokofiev’s music, “Russians love their children too”, the “cyborgs”, the war, Mertsalov’s palms in the airport’s interiors, flag on the ruins, convenient halls, a recognisable reality of the globalised world, sadness, and death… And suddenly a strong urge to arrive at this airport. A feeling of an irreversible loss of home. By the way, I’ve never been to Donetsk. The author, obviously, had not foreseen this reaction, for him, it was a reference to some distorted kind of video game, where good was fighting evil over different levels. And we both do not know what we to do with this knowledge about senses that connect us with the words “Airport Donetsk”.

And a couple more words about another message from the “Reconstruction of Memory ” exhibition which answers, in my opinion, the question why should we enter this torn space at all, instead of avoiding pain. A seemingly simple idea – “The Beach”. Pebbles from Crimea, scattered on the floor. And that’s all. It’s not only about this exhibit specifically attracting all those, for whom Crimea once was home (people used to come, sit beside, and hold the pebbles). It’s about the way this “Beach” was created. The pebbles were brought by people who kept them in their “treasure boxes” with memories from summer vacations, in a response to a plea the artists have posted on Facebook. At first, nobody was certain this will work out. What if nobody brought their pebbles? No, seriously – these pebbles were kept to remind of happy days. We all know, how important these small things can be? It’s quite possible, these people will never visit Crimea again. But eventually “The Beach” was successful. What made people bring their little treasures? The understanding that it would be important for others to come and hold the pebbles, pieces of their lost home. The sense of solidarity. The eagerness to share the common loss. I was shown a document that one of the donors wrote – “I, name, hereby donate thirty pebbles for the usage during the exhibition…” I asked, how they were going to tell which ones are theirs. A smile was the answer. Naturally, there is no way to tell them. It’s just that they were not yet ready to fully accept that they are giving away their little treasure. But it was important to make this project, more important than to safely store personal memories. That’s why it is worth entering this space of pain and loss – by sharing this pain we define the borders of our world. Our common world.

The feeling of layering senses was following me through the whole “Reconstruction of Memory” exhibition. One layer visible through another and one more, all together creating strange constellations of interpretations that cannot be read in the same way by different people.

“Reconstruction of Memory” is not only about displaced persons’ memories about their homes. It is an attempt to work out the language to speak about a joint self-understanding by those who identify themselves as a part of Ukraine. Memory is not for the past, it is for today and for the future. Crimea and Eastern Ukraine are, in the first place, our common pain, and common should be our attempts to soothe this pain. It’s a case of social solidarity – because only the inclusive conversation about our future opens for us a path into this future. A conversation of many voices – voices of people who tell about what they’ve lost and who ask about the losses of others, accepting them as their own.

Unfortunately, our lame historical memory swings from side to side and cannot decide who is going to be the next great hero whose gigantic monument will save our motherland. This historical memory has no language to speak about the past and present in a human scale. We keep searching for a perfect community to look up to, just like the soviet pioneers did. We will only be able to construct our future when we will learn to feel compassion for our compatriots who have lost their home, their past, their world, instead of just feeling anger because of territorial losses. To share the new neighbour’s yearning for the familiar sound of the siren in Donetsk is to make a step into the future.

“Reconstruction of Memory” is not a cry for help, it is a demonstration of the area, of how reloading the historical memory in Ukraine can be based on seeing each person and their experience separately. Historical memory, from now on, should be aware of this new area – the memory about lost homes that is shared by others as a common loss. It’s an issue of survival, of establishing new social relations. It’s not about crowdfunding (we’ve learned to do that in the course of these three years), it’s much deeper – we need to learn to see the new horizons of our world, which are not about superpersonal concepts, but about the notions of common troubles and the need for common actions. While we are at war and in fear, it is much easier to dehumanise everybody and to start operating with only general notions. But if we follow this path, we will lose our humanity.

1. Narsky I. Life in catastrophe. Population’s daily life in Ural in 1917-1922. Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2001, p. 632 (in Russian).

2. Waldenfels B. Alien’s motive. Minsk: Propilei, 1999, p. 46 (in Russian).

3. Ibid., p. 56.

4. Assman A. Reframing memory: Between Individual and Collective. Forms of Constructing the Past. In: http://gefter.ru/archive/11839 (in Russian).

5. Trubina E. Phenomena of secondary evidences: between indifference and “refusal of incredulity” // Topos, 2007, № 1(15), p. 114 (in Russian).

6. Hirsch M. What is postmemory? In: http://urokiistorii.ru/node/53287 (in Russian).